A Teachable Moment: Helping Students to Understand Permanence of the Digital Age

Surprised parents and staff members have been emailing me this week with a concern. Googling the keywords of our school district's name provides some information about the district along with an image that represents members of our student body, but not in the positive or academic light most of us might hope.

While there is a larger issue here of the district being improperly and unfairly represented in the public eye (we are presently working on a solution to this issue as we want the district positively and accurately represented for the meaningful teaching and learning that happens here), there is something we can use in this event to assist in a meaningful conversation with students and families.

With services like SnapChat and Instagram, Twitter, Tumblr, and Facebook, sharing with the world is easier than ever before. Especially with some of these services, but true for all, users often confuse the ability to instantaneously share with the world with the appropriateness of doing so. Add to that the sense of anonymity, the tidal wave of information that is being shared worldwide (as in "everybody is doing it"), and the false "promise" of the information existing only in the short term (services like InstaGram allow users to post to the world, but in very short intervals, as in 10-15 seconds, before the post is removed).

However, as so many of us are aware of, the truth is that once data is captured and posted in a public forum (and the Internet is a public forum), even if only for a few seconds, the potential exists for that data to live forever.

This is exactly how the image that presently represents our district in a Google search (not a decision consciously made by anybody in the district, by Google itself, but simply a result of an algorithm written and a change in the way Google presents information for ease of viewing), an image of some young people captured in a dance position while at a school dance that may have made them blush had their parents been present, came to be. It seems to have been captured and shared online, likely by a student interested in updating others on the fun of the evening. It probably didn't get much attention immediately. However, it was picked up in a story by a local news outlet about the appropriateness of student behavior at dances (not just our students...students across the area). That seems to have gained some traction with viewers, and the image has been viewed many times by many people. That moved the status of the image up in Google's search rankings. When the Google Knowledge Graph was created and launched publicly, the ranking of that image, coupled with the search term of our school's name, resulted in the "marriage" of the district's online reputation with a student's behavior at a moment in time. Something the students likely had not considered or even imagined in that moment.

As unfortunate as any of this may be, there is a teachable moment in this. In a digital world, our actions (both online and in real life) do not have the promise of privacy. While we may (or may not) disagree with this reality, it is still, in fact, a reality. This week's headlines about the availability of private digital data possibly available to government entities supports this reality.

Students need to hear that message -- in a digital world, our actions (both online and in real life) do not have the promise of privacy. They need to be engaged in the conversation. They need to consider how that information may positively or negatively impact them in the present and in the future. These are all meaningful discussions that we, as educators, cannot be afraid to engage in. Even if we are not technically savvy enough to know all of the latest digital tools, sites, trends, and methods. We have life experience enough to talk about the value of students holding themselves to a standard that they (and their families and communities) deem appropriate. We have life experience enough to talk about how decisions made in a weak moment today can forever impact our futures. This doesn't require knowledge about technology -- let the kids bring that knowledge and experience to the conversation. Instead, it takes us actively talking with kids and caring about their lives today, and in the future. And we do care!

That is the teachable moment in this.

Using Tagxedo to Visualize My Blog and Twitter Themes

When I was first introduced to tag clouds, I thought they were interesting, excellent for pulling themes from longer works (trying putting text from an entire chapter of a novel into a tag cloud generator...it is so interesting to see the results), great for analyzing redundancy of word use in original works, and it has some other unique niche uses.

One benefit I'm finding, though, as I publish and share more work digitally, is that the tag/word cloud generators give me a great idea of what I'm thinking (and writing) about.

I recently used a word/tag cloud generator called Tagxedo to evaluate the themes of this blog, Getting Tech Into Ed, and I combined that with my tweets for @brianyearling. I think the results are so telling of what has been on my mind over the past few years. It also made me think about how something like a digital portfolio and blog that a student produces for academic purposes could be turned into a wonderful reflection tool when it comes to a freshman or sophomore conference to determine next life steps. Perhaps the use of a tag/word cloud generator could pull some beginning themes out of what they've studied and written about that could influence the conversation and give them some ideas upon which to reflect. The same is true of an end-of-year conference with a teacher, a student-led conference, or just a reflection on a whole class blog.

The tool I used that produced the results below is www.tagxedo.com .

Setting a Good Example for Students Related to Internet Use

t is easy to forget the irritating little pains of the past. Most of us have LONG forgotten the dreadfully slow Internet access that was experienced district wide near the conclusion of the 2012-13 school year. Painstakingly slow connections that made viewing instructional videos nearly impossible, halted some of our virtual academy students school work in its tracks, and wasted precious instructional minutes. With our robust new Internet connection in the School District of Waukesha, we seem to have MORE THAN ENOUGH bandwidth to go around this year. Right?

This is just a reminder that your actions as a classroom teacher, as a supervising staff member, as a member of our professional community, matter. We model for kids. Kids watch us closely. Just as we teach them with our words, we teach them with our actions, as well as our inability to act when we should. With that said, the example below is just one example of a way in which we can all set a better example for students.

We all know that the college basketball event known as "March Madness" can be a lot of fun. This year's March Madness was even more special with Marquette and UW-Madison making it to the tournament. As seems to be the case every March, a dedicated few sports fans seem to find ways to keep tabs on the game in a wide variety of ways. While it is ultimately harmless fun (that can seem almost necessary by that point in the school year), what we often fail to see is the impact that Internet use has on those around us (across the entire school district).

The graph below demonstrates the bandwidth consumed in the School District of Waukesha during the time the first round of the 2013 NCAA Basketball Tournament was being played. The red arrows and vertical red lines on the graph indicate the beginning and end of the basketball game played on that day.

Points worthy of noting:

- The bandwidth consumed in the final moments of the game is more than 10x the TOTAL bandwidth AVAILABLE in the district during the last school year

- Though our bandwidth use in general is about 4x higher this year than last year (a sign that our educational use of the Internet is far greater than what was even available last year), during the game our bandwidth use jumped substantially, and then returned to normal levels following the conclusion of the game (indicating an excessive amount of viewership for some event that happened within that time period...see if you can determine what it might be)

- Almost all of the traffic reported came from two sources, both of which were broadcasting the NCAA tournament at that time.

- 2 - 3 times the normal Internet traffic consumed during this period was streamed to about 130 users across the district -- that is approximately only 1-2% of our total number of users across the district

- Despite our incredible 1 Gig connection (an incredibly robust infrastructure in any school district), we topped out our usage. This is same situation that took place near the mid to end of last year that caused the haltingly slow Internet speeds across the district.

While it is easy to track these stats on a day when we can predict additional bandwidth usage, such as during March Madness, the reality is that many of us have daily Internet use habits that chew away at the bandwidth intended for meaningful teaching and learning. Whether that is having Pandora or iHeartRadio streaming all day in the background, watching Netflix or YouTube, maintaining constantly open windows with Tumblr, Facebook, and other services, or using the network for a wide variety of other uses not focused on education, the reality is the same -- your actions on our network impact others directly.

As we gear up for Waukesha One, which will see a major influx of devices hitting our Internet connection, it becomes even more important for us to set a good example for students. Asking a student to turn off a gaming site or a streaming radio station is much easier when we avoid using similar services ourself. Instructing a student to turn off his/her sporting or gaming event of choice is a more clear cut conversation when we have resisted the temptation to turn on that March Madness game while at school. This conversation will become even more relevant as we see our regular use of the Internet grow significantly as we make a change to more digitally focused teaching and learning.

All Internet use contributes to our overall bandwidth consumption! Overusing our Internet resources for non-educational purposes ultimately slows down the access for all -- including for teaching and learning. Set a good example. Help your kids see why educationally relevant use of the Internet matters at school. Protect one of our most valuable resources!

Breaking Down the Classrooms Walls for Professionals

One of the unforeseen blessings of having an educational role such as ours, Instructional Technologies Coordinators, is the opportunity to regularly visit the classrooms of so many professional educators on a daily basis. I regularly learn more about becoming a better educator during these visits than I could have ever learned through years of "trial and error" in my own classroom. It is one of my greatest regrets that I did not seek out more opportunities to observe the professional practice of my colleagues when I was a classroom teacher.

One of the unforeseen blessings of having an educational role such as ours, Instructional Technologies Coordinators, is the opportunity to regularly visit the classrooms of so many professional educators on a daily basis. I regularly learn more about becoming a better educator during these visits than I could have ever learned through years of "trial and error" in my own classroom. It is one of my greatest regrets that I did not seek out more opportunities to observe the professional practice of my colleagues when I was a classroom teacher.

At Waukesha North, a healthy culture of collaboration has been embraced throughout the building. As a key element of that, staff members are beginning to seize the opportunity to step outside of their own classrooms and to place their professional learning front and center, as they learn from their colleagues. Calling them "learning walks" or "instructional rounds," the goal is consistently the same -- learning to improve the craft of teaching by observing, reflecting, asking questions, and implementing.

Principal Jody Landish recently published a thoughtful, sincere, inspiring post about the instructional rounds taking place at North. Read her reflections related to the value of this level of collaboration and professional learning on her blog post - Instructional Rounds in Education -- Principal of the Purple Palace blog.

A Thing or Two to Teach Our Kids About Technology

I'm fortunate to have colleagues from around the district feeding me great articles when they find them. This article, forwarded to me by Butler teacher, Mollie Heilberger, points to a critical point of conversation. Thanks, Mollie, for bringing this to my attention.

A recent article from the New Tech Network blog serves as a reminder to us that just because a student is born in an era where technology is omni-present, that doesn't necessarily mean that they are innately knowledgeable about how to use that technology productively for academic or professional pursuits.

Digital Native Does Not Mean Digital Literate

The blog post talks about a false assumption that we are all increasingly at risk of making about our students. The assumption asserts that simply because our youth have grown up in an era where the Internet, computer access, Google, and Facebook are readily accessible, our kids innately know how to utilize the tools for meaningful academic work.

It is no wonder that we make this assumption. For many of us, our lack of comfort with technology, mixed with the popularity of that same technology with most young people (I dare you to find one who doesn't regularly use a smart phone, or at least know how a smart phone works) leads us to believe that young people somehow just "get it" when it comes to technology. Mix that with a little bit of naive, misguided confidence on behalf of many young people in masterfully using various forms of technology (I dare you to find a classroom of kids that doesn't have a least one "expert" technologist on software he/she has never used before in his/her life), and it's easy to understand why we tend to trust that somewhere along our genetic lineage a dominant technology trait was formed and turned on with the invent of Google.

This is NOT to say that kids don't have some mad skills when it comes to the use of technology. Some of them do -- many do. More importantly, they have never known the fear of "breaking it," which hinders/paralyzes so many adults when it comes to technology use. It simply means that we cannot assume that they all have the same comfort with technology, or that they all can use technology for the deeper side of research that they need to engage in to meaningfully learn.

There are still many valued lessons that come with age, wisdom, and experience that teachers bring to the academic experience. These skills and lessons transcend medium -- no technology comfort or expertise required to put these skills to work. That is at the core of what we must offer our students as we work with them. It is the guidance that they need as they employ the digital tools that are at their fingertips to do the hard work of learning.

And it is in that gap between our discomfort with technology and their lack of life and academic experience that students and teachers can meaningfully connect to teach and learn from each other. This is where teaching Essential Skills, such as digital citizenship and research come into play. They may not be measured on standardized tests, but they are the skills that will ultimately help students to fail/succeed in lifelong pursuits.

So, the next time you integrate some element of technology into your classroom practice, don't be afraid to spend some time teaching the kids a thing or two about how to use the technology to become more academically, professionally, and personally productive with the tools.

The e-Submission Insanity: Taking Control of Digitally Submitted Work -- Part 2

In our last article, we talked about the importance of crafting (and insisting upon) a naming strategy for digitally submitted work. This alone can be a valuable management strategy, but staff can put other measures in place to maintain a sense of sanity as more student work is turned in online.

This post focuses on a Folder Sharing/structure solution within Google Drive.

The Folder Sharing Concept in Google Drive

One of the core truths in Google Drive is that when a folder is created in Drive, the "properties" set for that folder are transferred to any documents or files within that folder (unless otherwise specified).

"Properties" refers to a few key elements when a user clicks the "Share" button on a folder or document in Google Drive:

- Whether that document is "Private," available to people within the domain, or open and available to the world, and

- Who specifically is being invited to view, edit, and comment on the document

The Folder Sharing Concept, then, focuses on using this principle to eliminate later confusion/frustration as students create one folder, set the sharing and viewing properties properly once for that folder, and then simply place all course related work in that folder for the rest of the year. This keeps an open line of communication between the student's course folder, and the teacher's access to that folder.

Setting Up Folder Sharing with Students

It is recommended that a teacher launch the Folder Sharing system with all of his/her students at a time when it makes sense to change fundamental operating procedures within the classroom. Moving all students at once to this system will make the transition cleaner and more manageable for the instructor. It also allows the classroom culture/expectations to shift at once.

Step 1: Develop a clear folder naming practice and general sharing guidelines to achieve consistency

- How do you want student folders to be labeled? (For student's organization, do more than just their name! Especially if they have more than one teacher.)

- Last Name, First Name - Subject

- Last Name - Teacher Name

- Last Name, First Name - Subject - Semester

- Do you want folders inside of that folder (nested or sub folders)?

- What level of sharing would you like students to give you? Viewing? Commenting? Editing?

- Editing is recommended...it gives you fullest access to the folders and files

Step 2: Create a "Class Folder" for your class(es) in your Google Drive

- Once students share a folder with you, it will benefit your efficiency to place those folders into a collective folder. Name the folder with clear identifiers, though. "American Lit - 2012 - Sem1"

Step 3: Reserve a lab/cart/computers and have students create the folder as a class

- While students can create this independently, it is worth the time and effort to be present to answer questions and to make sure the folder is set up properly the FIRST Time.

Step 4: As students share the folder with you, check the properties and drag into your "Class Folder"

- When the file arrives in your inbox, or in your Google Drive folder (look in "Shared with Me"), take a look at the properties to be certain they are set properly. Then, simply drag the folder up into the proper "Class Folder" in your Google Drive.

- You will not delete student access to the folder in dragging this into the "My Drive" section of Google Drive. It simply makes it easier for the instructor to find like student folders.

Step 5: Instruct students to place all work that is to be digitally submitted into that folder

- Remember that all files within that folder will take on the "properties" of the folder, unless otherwise specified by the student.

- Developing a file naming structure/code for the files in each folder will further assist instructors in efficiently assessing the work within that folder.

Tips to Teachers

While the system is fairly simple and easy to use, there are some strategies that will make this work more seamless.

While the system is fairly simple and easy to use, there are some strategies that will make this work more seamless.

- Clear initial expectations will ease the student transition to a new turn-in model. Avoid accepting paper versions of the work when possible if the expectation is primarily electronic submission.

- Prior to using Google with students, determine if they have an active Google account with the district. The easiest method is to have students attempt to log in.

- Encourage students to share their folders with a parent/guardian as well.

- Even without a Google account, parents can view (and even comment/edit) the work. Here's a link to an article explaining options for sharing with non-Google users.

- Use commenting on docs shared with you to provide feedback. Printing assignments and placing feedback on the printed copy defeats the purpose of e-submissions (and creates another step for you -- so much for efficiency gained).

- Engage students in a discussion about the work using the discussion tool in Google Docs.

- Check in often. You'll be amazed at how quickly work piles up. Even when it isn't due!

The e-Submission Insanity: Taking Control of Digitally Submitted Work -- Part 1

There are tradeoffs for everything.

The "paperless" world of electronically submitted assessments/homework is truly a gift for those of us who struggle to keep tabs on the zillion+ sheets of paper we collect each year.

Yet, the tradeoff is having to develop a new system for management of our digitally collected student work. For many educators initially encountering Google Drive, or other collection tools for electronically submitted work, you may have this overwhelming feeling that your digital work environment is no more functional than a cluttered work space in the physical world.

Ready yourself for the good news! By adopting a few simple strategies, and by training your students to use those strategies religiously, you can regain your own sanity and become far more efficient in collecting and providing feedback on digital assessments.

Developing a Consistent Naming Convention

For many teachers, the process of paper collection has become a carefully crafted venture, At the very least, most teachers have a protocol for students when it comes to turning in physical papers. Name on the upper right of the page. Hour, period, and/or date just below that. Top left margin has assignment name. For many teachers, a similar naming/identification process has become the only way to keep tabs (and our sanity) on the flood of paperwork we consume regularly.

The movement to a digital collection platform will not shirk the need for a digital naming/identification equivalent. In fact, without identifying some sort consistent convention, and then STICKING TO IT, you may not be able to take advantage of some of the other niceties of digital collection (automatic time-stamping when assignments are collected, search and sort functions to easily find text within specific documents, and more).

The most beneficial naming convention in a digital platform is one that places the critical data in immediate view of the teacher without having to open the file/document to find the data. Generally this is done best in the document's name.

One example of a properly named document might be:

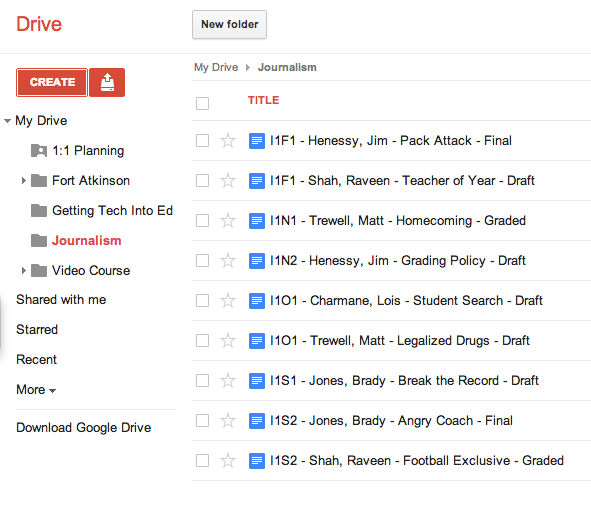

An example of a Google Drive folder when students have used a a standard file naming convention to submit work.

An example of a Google Drive folder when students have used a a standard file naming convention to submit work.|

What is an assignment code? |

- The teacher is "under the gun" to provide prompt responses, so he/she is constantly opening files to see the status of the work (many kids will submit the work to you before it is done...we'll talk about that as well in a follow-up post). Much of that work is incomplete, leading to teacher frustration, and/or wasted teacher time. In this scenario, we've lost all of the efficiency of a digital turn-in system.

- Response time to student work is dramatically hampered because the teacher sets an arbitrary date for "review and response" to maintain sanity. As a result, students fall into the same old habits of waiting until the last minute to complete work. We've now lost momentum and enthusiasm for a more personalized, fluid turn-in system. This system is truly no different than a system where students turn in work physically on the due date and await the teacher response.

- Draft: This meant that the student had not completed the work and was not awaiting my feedback as an instructor. For me, this meant that I did not need to open that document and offer feedback at this time, unless the student communicated with me personally and asked for assistance.

- Final: This meant that the student had "completed" the work and was awaiting my feedback. As soon as I saw "Final" in the title, I opened that document and began to comment and assess. I did this even BEFORE official due dates, as the student was indicating he/she had submitted his/her best work at that time.

- Graded: I renamed the file "Graded" when I was finished offering feedback to the student. It was an indication to the student that there was some level of feedback in the document for the student. Even if I was sending them back to complete another draft with revisions, I indicated graded. When the student switched the work back to "Draft," I knew that the student had accepted my comments and was going to try again. Other students accepted the grade that I offered and elected not to revise, leaving the code "Graded."

As always, you will have to flex for some students. Be aware that some students are having their own struggles adapting organizational strategies to a digital world. The most important factor in all of our work is student learning -- a rule or naming convention should never get in the way of a student demonstrating what they have learned. Flex when you need to. Getting 95% of the students on board with your system will make managing the unique cases more palatable.